中国绘画

Chinese painting is one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world. The earliest paintings were not representational but ornamental; they consisted of patterns or designs rather than pictures. Early pottery was painted with spirals, zigzags, dots, or animals. It was only during the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) that artists began to represent the world around them.

Painting in the traditional style is known today in Chinese as guó huà (国画), meaning 'national' or 'native painting', as opposed to Western styles of art which became popular in China in the 20th century. Traditional painting involves essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black or colored ink; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made of are paper and silk. The finished work can be mounted on scrolls, such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Traditional painting can also be done on album sheets, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, and other media.

The two main techniques in Chinese painting are:

- Meticulous - Gong-bi (工筆) often referred to as "court-style" painting

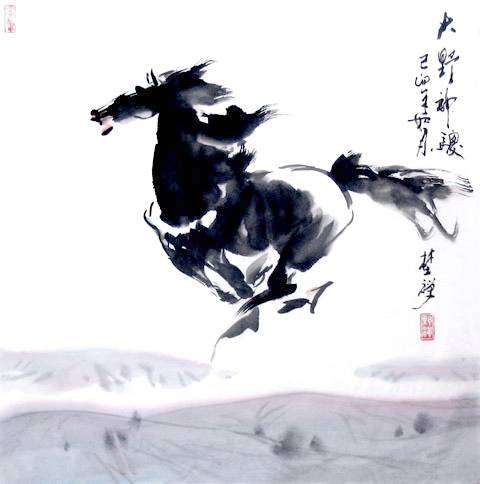

- Freehand - Shui-mo (水墨) loosely termed watercolour or brush painting. The Chinese character "mo" means ink and "shui" means water. This style is also referred to as "xie yi" (寫意) or freehand style.

Artists from the Han (202 BC) to the Tang (618–906) dynasties mainly painted the human figure. Much of what we know of early Chinese figure painting comes from burial sites, where paintings were preserved on silk banners, lacquered objects, and tomb walls. Many early tomb paintings were meant to protect the dead or help their souls get to paradise. Others illustrated the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius, or showed scenes of daily life.

Many critics consider landscape to be the highest form of Chinese painting. The time from the Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song period (907–1127) is known as the "Great age of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such as Jing Hao, Fan Kuan, and Guo Xi painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough stone. In the south, Dong Yuan, Juran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

刘阳的沂蒙画派

刘阳,北京人,现旅居海外。曾于中央美术学院、新闻学院、中国社会科学院及国外学习。曾在中央电台任记者、节目主持人,在大学任教。于国内外出版个人专著几十部,应邀举办个人画展五十多次。1986年至今开创沂蒙画派。

刘阳,北京人,现旅居海外。曾于中央美术学院、新闻学院、中国社会科学院及国外学习。曾在中央电台任记者、节目主持人,在大学任教。于国内外出版个人专著几十部,应邀举办个人画展五十多次。1986年至今开创沂蒙画派。

红高粱

黄昏秋色

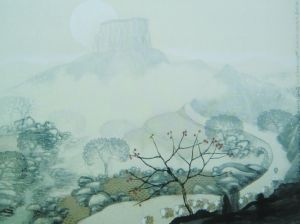

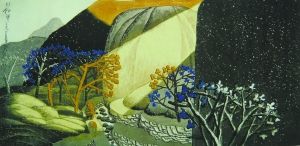

拾秋图

问斜阳

艺评

亿豪(香港)

作为出生在20世纪的开宗立派的中国艺术家,进入21世纪,刘阳先生对中国绘画进行提纯的思考,将他的整体艺术思想技巧体系,进行着纯粹化的提纯,有如张艺谋、陈凯歌、冯小刚等人对电影的提纯,崔健、谭盾等人对音乐的提纯……这样的过程刘阳先生也经历了几个时期,一,20世纪八九十年代通过对中国书画理论的提纯,形成并完善他的艺术思想体系,开创沂蒙画派与人体山水画,通过运用光色与符号形成观念上对技巧的提纯,并确立他艺术综合价值体系;二,21世纪初,对体裁、观念、技巧的提纯,刘阳不是表现自我,也不是克隆自然,而是在看似回归,确是不断挖掘与丰富中国特质的绘画,通过用笔、水、墨,黑、白、灰的极致,在中国的宣纸上像小说家、音乐家一样,为每一山、一石、一树、一草、一水、一屋、一人作传。谱一曲永恒的旋律。

刘阳先生的艺术纯粹,源于他心的纯粹。每观一山、一石、一树、一草、一水、一屋、一人,他都全在心中自语为什么会是那样的?然后他开始在地理学、语言学、民俗学、建筑学中找答案。然后他开始用毛笔、水、墨在中国宣纸上将“那样”弄成“这样”,用时间、精力、思想,表达对过去的、现在的、未来的、存在的、消失的珍惜,精神与价值的重温与回顾。

文化之外,刘阳先生注重对人格、艺格的升华。他对纯粹的认识,如用虎跑的水、沏龙井的茶,作为这一代中国艺术家,刘阳多年坚持从北到南、从东到西,大范围地精选,透彻地深入,有价值地表现中国不同地域风情、山水、人物、花鸟作品。他的沂蒙作品独辟蹊径自不必说,他的江南与云贵、青藏高原系列,更是“致广大、尽精微”(中国现代艺术大师徐悲鸿先生语),从对自然环境、风物人情的把握、刻画到宣纸上笔墨的锤炼,创造并强化了中国绘画的直觉、感觉,从无到有的实在,再从有到虚灵,信手拈来,那种纯粹的自由自在,有如弹指间的拈花微笑,有如睡眼蒙眬的一瞥,有如不经意的一句幽默……令人回味,虚而不悬,实而灵隐。每幅作品都纯粹得像诗的、歌的、梦的、心的、灵魂的家园,每个人都可以从中发现过去的失去的自己,发现过去的失去的回忆,提示与敲点人性深层的冷暖,有如好莱坞大片,每一帧都透射出东方的、中国的精神,这其中有历史与地域的呼吸、深叹,有光与色的希望,有发现与拾拣的快乐。

东方与中国艺术精神到底是什么?与西方有什么区别?达尔文关于物种的区别是最好的验证。既然有这样的人种、物种,并由此产生的历史文化、价值观念、行为差异,除了“适者生存”便应该是进化的提纯的纯粹化了。

东西方的隔阂本质上是“种”的差异,选择了“种”,也就选择了生存状态与品质结果,那些在历史上曾产生并消亡的动植物,都是由于主动的“适”与被动的“不适”,导致了无数的悲喜剧。只怀念历史与文化益处不大,再用已过去的历史文化,去设定现代化与当下的艺术及价值标准是不纯粹的。

提纯的纯粹过程与结果,甚至是极限与临界的转化,是多维度的考量与体验,有如佛家修行从禁食到闭关辟谷,是对生的、肉体精神的、灵魂的虚化提纯过程,并非简单的写实与抽象的玩赏,也正合物质财富的从无到有、从多到质的飞跃。

纯粹犹如煮饭淘米,犹如吃、喝、拉、撒、睡……是将复杂简单化的过程,这个过程,是对能力与涵养的考量。

纯粹是一种境界,是智对愚的净化过程,是规范与优胜劣汰的过程,是重生与再生,是价值的产生与提纯,刘阳先生的艺术如此。